Towards Futarchy in Tezos

Futarchy, in a nutshell, is the governance technique of evaluating policies ex post while relying on a prediction market to determine the best policy ex ante.

The Tezos position paper explicitly mentions futarchy as a possible development for the governance of Tezos. This blog post presents some concrete ideas for its implementation.

This leads me to an important point: regulations should not, and do not curtail research and development of novel governance technologies. However, in order to ensure the successful deployment of those ideas one should be particularly mindful of the regulatory landscape so as not to run afoul of applicable laws. In order for these technologies to benefit as many people as possible, the best path forward is education, and engaging in constructive dialogue with regulators and lawmakers around the world.

One more note, economist Robin Hanson coined Futarchy and deserves all the credit for introducing it as a governance mechanism and researching the machinery required to make it work. Whichever fraction of the total credit he feels is worth re-crediting is his to reassign.

A quick primer on prediction markets

A prediction market is a financial tool for efficiently crowdsourcing predictions. The general idea is that the price of a financial asset reflects the discounted, risk neutral, expectation of a payoff. Stocks pay dividends, commodity futures lock in a price for purchasing commodities, etc. In these markets, traders can invest their time, money, and skills in order to detect mispricings (i.e. mispredictions) and trade accordingly. These trades move the market until the mispricings become smaller than the expected opportunity cost of detecting them.

The term prediction market is typically applied broadly to markets whose payoff isn’t tied to a financial instrument. The payoff could be binary, based on the outcome of an event, for instance: “Will Republicans control the senate in 2018?” or “Will France win the world-cup in 2022?”. It could also be a more continuous payoff, for instance “+$1 for each degree over the seasonal average for NYC in 2019”.

Financial instruments aren’t just traded in a zero sum speculative game. For instance, stocks are held for investment purposes, commodity futures can be bought by producers and consumers to hedge their exposure. Contracts whose payoff is based on the temperature do exist and are traded on the CME, albeit thinly. They can help electric utilities manage costs by predicting air conditioner use, or they can help landlords manage the variability of heating costs. Sport bets on the world cup also have an intrinsic utility: they make the games more exciting to watch!

A pretty stock picture of some order book and candle graph

A pretty stock picture of some order book and candle graph

Interestingly, financial economics teaches us that this demand (investment, hedging, insurance, entertainment) is required for the markets to exist among rational actors. This principle is called the no-trade theorem.

To explain the no-trade theorem, imagine a game of Texas hold’em poker with no blinds. Of course, some players would play such a game (they would gamble), but an astute player would simply fold every hand until they hit the nuts, two aces. However, an equally astute player on the other end of the table would always fold in such a situation, knowing that the move indicates the other player has the nuts, unless of course they have the same hand. The no-trade theorem goes the same way. If there are no intrinsic reasons to trade on a market, the outcome is rational traders staring each other down, assuming that any bid indicates superior information.

This result should not be a surprise. Making accurate predictions requires time, money, skills — all of which represent direct costs or opportunity costs. Someone has to be paying for all that research. In the stock market, the research is paid for by investors who cross the bid-ask spread thereby compensating market-makers for the money they lose to informed traders. In sports betting, it is paid by uninformed gamblers who cross the spread for the thrill of the game or out of delusion.

Paradoxically, noise traders who buy and sell without sufficient supporting evidence make markets more accurate by subsidizing price discovery. However these traders can come and go, and it would seem imprudent to rely on their presence to harness the predictive power of these markets. The most natural way to subsidize price discovery in a market is to pay market makers to maintain tight, double sided quotes. A naive market maker constantly offering to buy or sell with a reasonable spread will naturally lose money to informed traders. Paying the market maker permits funneling a subsidy towards the most efficient forecasters.

Futarchic governance on Tezos

Futarchy is a tool and there are several ways it could be applied in Tezos. In the following blog post I have attempted to move towards a more concrete proposal for futarchic governance in Tezos than the one outlined in the position paper.

As Hanson puts it, the idea of futarchy is to “vote on values and bet on beliefs”. The idea is that values should reflect the subjective goals and preferences of the group sharing the resource being governed while determining the policies best suited to achieving those goals is best left to a more “objective” prediction market. Several markets can compare the expected merit of different policies and thus suggest the one to adopt.

This leaves two questions open: where do futarchic decisions fit in the Tezos governance process, and what can those values be.

Belt and suspenders governance

In the current betanet governance, participants select amendment proposals through approval voting, hold a vote to decide on the proposal itself, and a bit later a confirmation vote. A natural approach would be to maintain the last two votes, but replace the approval vote with a futarchic based ranking. This has the benefit of leaving the vote as a solid check against possible failures of the futarchic process.

In general, I believe that the conjunction of distinct governance processes generally compounds the benefits of each system and not the flaws. This “belt and suspenders” approach stems from the observation that governance procedures have more false positives than false negatives. A worthwhile proposal is likely to appear worthwhile under most lenses while a bad proposal may make it through only a few governance models. A demagogic proposal that would pass a vote may not pass the muster of a prediction market. A clearly adversarial proposal designed to slip through a blind spot of futarchy may not fool voters.

This is not a free lunch: In the limit, if too many filters are applied, even good proposals may be rejected. The cost of introducing too many layers of governance too quickly is premature stasis. However, I believe this to be a very cheap lunch.

Values

What do participants in the governance process value and how can we measure it? Let’s start with a few observations:

First, there isn’t necessarily a well defined answer to this question. There is no principled, meaningful way of aggregating individual preferences. However, preferences roughly point in the same direction. There is no rigorous, ironclad, definition of what exactly constitutes a birthday cake, but that shouldn’t stop people from baking them. Our inability to formalize the concept may reflect as much on the limits of our formalization abilities as on the concept itself.

Second, an approximate proxy to the value may be sufficient. While optimization processes do tend to produce negative unexpected consequences when they are not optimizing exactly for the actual goal, the Tezos governance process is nowhere efficient enough to enjoy the luxury of having this problem.

With those observations out of the way, several reasonable metrics come to mind. Some are intrinsic and can be computed on-chain, others are extrinsic and require the use of decentralized oracles.

On a proof-of-work chain, a simple intrinsic metric could be hash-power as a reasonable proxy to the health of the network. However, it’s not a very good fit for Tezos which relies on a proof of stake.

A simple, elegant, and intrinsic metric proposed by Ralph Merkle in 2016 is to rely on an ex post vote. Participants may not be good at deciding ex ante *what is a good policy, but deciding out *ex post if a decision was a good call is much easier. Instead of making a decision, the participants are asking the prediction markets to determine what policy they are likely to be satisfied with in the future. This isn’t perfect, but has the benefit of being clean and simple to implement.

Extrinsic metrics

Extrinsic metrics are also possible, but they require an oracle to provide “off-chain” information. This oracle could be centralized, for instance, if Tezos participants wanted to maximize the number of pandas in existence, they could entrust the WWF to provide this data to the blockchain. If they wanted to maximize adoption, they could task several auditors to estimate the number of individual participants. However, if the metric is more easily publicly verifiable, they could rely on a decentralized oracle to import that number into the system.

A general technique, for the oracle to propose a number, is to run a game where participants can place hidden bids onto a candidate number. After the bids are placed they are revealed and the tokens are redistributed according to a formula which rewards proximity to the median, for instance something proportional to 1/(1 +(choice-median)²). If the true value isn’t particularly controversial, a natural Schelling point in this game is to play one’s true estimate.

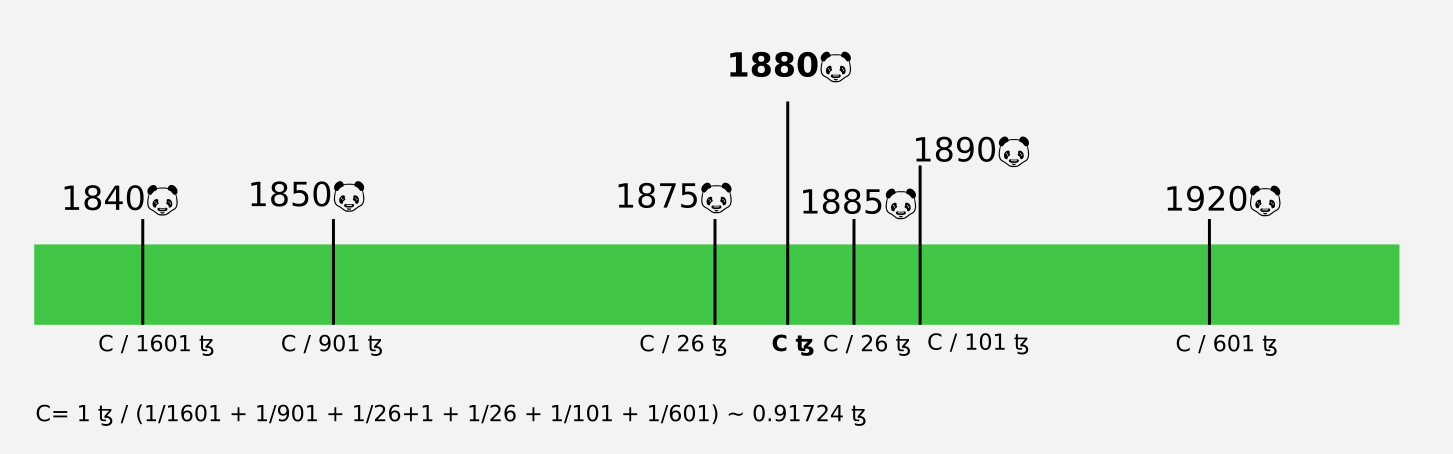

A run of a decentralized oracle enabling panda-centric futarchy

There are known issues with this approach. In particular, a wealthy participant could make a strong, public commitment to back the wrong number and create an avalanche where his choice becomes the new Schelling point. A patch would be to offer voters the possibility to force a “do-over” if the settlement is rigged. It does improve things a bit, but it isn’t perfect.

Alternatively a body could be elected to devise and compute a metric, with provisions to override their decision.

Meet Leo, the panda.

Meet Leo, the panda.

Measuring expected outcomes

Assume a metric has been picked. For the sake of generality, we’ll pick a continuous metric as opposed to a binary one, as this represents the harder case, call it “x”.

In the governance model we described earlier, several competing proposals are being analyzed by a prediction market. However, at most one of these proposals will be adopted in this cohort. How do we settle the prediction markets for the other ones? If we do not implement policy P how can we tell who was right and wrong about the effect of P on x?

Conditional markets

The solution is to make two predictions: one on the probability of proposition P being adopted, and one on the value of x conditional on P being adopted. You can think of the first market in terms of tokens.

Consider a token called XTZ_P, which pays out 1 XTZ if P is adopted, and token XTZ_!P, which pays out 1 XTZ if P is not adopted. By a no arbitrage argument, 1 XTZ_P + 1 XTZ_!P = 1 XTZ. Likewise consider a token XTZ_P_x which pays out x XTZ if P is adopted and 0 XTZ otherwise, where x is the ultimate value of metric x. Another way to look at it is that XTZ_P_X unconditionally pays out exactly one x XTZ_P token.

Form the ratio XTZ_P_x / XTZ_P, i.e. how many XTZ_P tokens does it take to purchase one XTZ_P_x contract. By a no arbitrage argument, this value should measure the expected value of x conditional on P being adopted. This estimate can be quite noisy if the proposition is unlikely to be adopted. Fortunately, we care about precise estimates for the propositions which are likely to be adopted. If a numerical instability led XTZ_P_x / XTZ_P to be overestimated, XTZ_P would actually rise, dissipating the numerical illusion.

Market structure

How should the market for those instruments itself be structured? It’s not enough for these instruments to exist, a price must be formed, and it must be observable, on-chain.

The most common market structure is the continuous double auction, where traders place bids and asks in an order book which matches crossing trades. This is the market structure adopted by most exchanges and it permits continuous trading. Another common structure is a batch auction, where orders are submitted blindly, and then crossed with each other at a price which maximizes the amount matched.

Continuous markets are useful for traders who want the convenience of buying and selling at all times, but are they really necessary for futarchy, where we solely care about forming predictions? A simple approach would be to hold a single auction, where traders submit their orders into a smart-contract, forming a single price used for predictive purposes.

While this has the benefit of simplicity, it carries a serious drawback: traders cannot observe and react to mispricings. In a continuous market, mispricings can attract the attention of traders with superior information who come in and correct the deviation. Furthermore, a naive single auction does not let traders express beliefs about the relationship between various events being bet on. Doing so requires the complexity of combinatorial market. A continuous market does not depend on combinatorial bets being available, as those bets can be placed in real time, one leg at a time.

Microcosm of London — Auction room, Chritsie’s

Microcosm of London — Auction room, Chritsie’s

Ultimately, finding the best structure is an empirical question. In the interest of concreteness, as a first shot, a reasonable structure would be to hold five, one hour long, batch auctions over a period of two weeks. This is assuming there are at most 10 proposals being considered simultaneously. This is unlikely to be optimal, but it’s also unlikely that further research would yield radically better outcomes.

Automated market making

As mentioned in the introduction, a key to extract good forecasts from prediction markets is to subsidize market making. In Tezos, this can be done through inflation by issuing new tokens to automated market making contracts.

The goal of these market making contracts is to provide liquidity and lose their subsidy to informed traders who will push the price towards a good forecast. What strategy should our automated market making contract follow? Let’s forget about outsmarting other traders, a reasonable goal is inventory management. So long as the market maker does not run out of money, it will be able to provide some quotes, so let’s try to keep our pockets full.

Assume the market maker initially sits on n XTZ, these can be converted into n XTX_P tokens and n XTZ_!P tokens. Denote by a the quantity of XTP_P tokens in the inventory and by b the quantity of XTZ_!P tokens in the inventory. Initially, (a=n, b=n).

In order to maintain its inventory, our market maker will try to maximize ½(Log(a) + Log(b)). This is a simple way of expressing a preference for not running out of either side of the bet, but it’s also equivalent to saying the market maker believes the event has a 50% chance of happening, and has a logarithmic utility.

How much should we charge to sell 1 XTP_P token? Suppose we receive q XTP_!P tokens, we will charge a price that leaves us indifferent. Log(a - 1) + Log(b + q) = Log(a) + Log(b) => q = b/(a-1). Conversely, we should be willing to pay b/(1+a) XTZ_!P tokens to buy 1 XTZ_P. The probability estimate is then given as b / (2 a ). That is, if the market maker ends up owning a lot of the XTZ_!P contract, it is likely that P will be adopted!

Following this algorithm, the market maker will let its quotes be pushed around by the flow. While the market maker may be wrong about its utility function, it is consistent and thus cannot be gamed… it will lose money to informed traders, but uninformed traders cannot systematically extract money from it.

It is possible to devise better algorithms that take into account the time remaining. The techniques are based on optimal stochastic control. However, the algorithm above is dead simple and a good first approximation. For more color on the topic, see Hanson, R. (2002). Logarithmic Market Scoring Rules for Modular Combinatorial Information Aggregation.

Next steps

We’ve covered the main aspects of a futarchy proposal in Tezos. This proposal needs to be further refined by filling a few gaps. Which specific measure should be maximized? When should the market resolve? Resolving markets before the adoption of the proposal prevents gaming of the mechanism through proposals that change the market resolution code, but resolving them later gives more time for the policy to make an impact on the value being measured. How large should be the market subsidy? Should the market for all proposals be subsidized? Should a round of approval voting be used to decide which market should be subsidized? Perhaps a fixed number of proposal slots should be periodically auctioned on the network. Fine-tuning all these details is a painstaking task as this is new ground and there are few antecedents to go by.

Thank you to all the people who helped me refine this piece. I’d love to list your name if you do not mind the (minor) loss of privacy.

](/assets/images/oracle_delphi.jpeg)