Why government debt should be issued as perpetuities

Note that the following idea isn’t particularly new, economists have known this for a while. I only happen to think it ought to be better known. When it comes to bonds, perpetuities are a great idea. One of their advantage is that new and old issues are fungible, provided that the coupon payment dates debt align. The downside is that the duration of such a bond is fixed and depends solely on the interest rate curve.

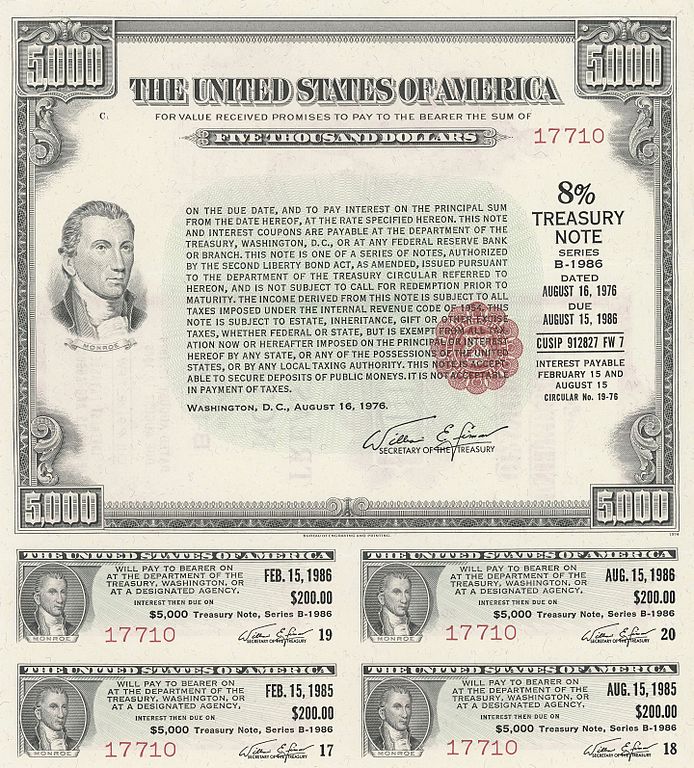

United States 1976 $5000 8% Treasury Note

United States 1976 $5000 8% Treasury Note

However, one can issue a perpetuity where the coupon is set to decrease (or even moderately increase) geometrically over time. Different issues of such bonds are still fungible (provided they use the same rate of exponential decay), but their duration can now be tuned at will, by changing the characteristic time of the exponential decay. Why does this matter? There is a large market in government bonds (particularly in the US) and this market places a large premium on the latest issued bonds, sometimes called “on-the-run”. This is because these bonds enjoy the most liquidity and can be used as alternatives to cash. The premium gradually disappears as the bond is replaced with a new issue.

The lack of fungibility means that real economic value is being destroyed. Beyond the premium placed on those bonds, less liquidity means that many potential mutually beneficial trades do not happen. Perpetuities with exponentially decreasing coupons would immediately solve that problem.

One might wonder what schedules are possibility beyond geometrically varying coupons.

Assume we have a market with n different perpetuities: \(p_1, p_2, \ldots, p_n\). When we shift the coupon schedule of any of these securities in time, we would like the resulting security to be expressible as a linear combination of the n perpetuities. \(p_1, \ldots, p_n\) should be the basis of a vector space of coupon schedules which is stable for time shifts. As it turns out, any vector space with this property will be the sum of spaces spanned by \(\{ e^{\lambda t} t^k | k < K \}\) or \(\{ e^{\lambda t} t^k \cos (\mu t), e^{\lambda t} t^k \sin (\mu t) | k < K \}\) for \(\lambda, \mu\) real.

This can be seen by taking the Jordan Normal form of the matrix expressing the constraint.

The nice thing about this is that it lets us issue bonds with longer duration than a perpetuity without taking the risk of growing coupons too aggressively.