What do blockchains accomplish

What do blockchains accomplish?

In the wake of Bitcoin’s success, many have predicted that a part of its underlying technology, the blockchain, could power many other types of applications.

Blockchain technology may indeed pioneer many innovative applications. However, to harness its benefits, one must understand the fundamental technical problem they solve. Though many problems can be solved using a blockchain, few derive any benefit from such an implementation.

What are blockchains?

The formal definition of a blockchain is a subject of contention. In this post, I adopt the following:

Blockchain: a data structure representing a consensus record as a series of operations bunched into blocks and validated according to a cryptographic protocol by a set of participants. It is used to implement distributed and even decentralized ledgers.

There are other definitions of blockchains, some of which specify that the consensus forms through economic incentives and some of which further restrict the consensus mechanism to the proof of work scheme introduced by Bitcoin. These definitions aren’t wrong, and the word “blockchain” itself is too recent to assert that one acception is the most appropriate one. I prefer to take a more encompassing definition, as there are otherwise no good words to describe some of the systems that have been suggested. Since the purpose of this post is to illustrate some limitations in the usefulness of blockchains, the argument applies a fortiori to the narrower definitions. In fact, the argument applies to an even broader class of systems: distributed ledgers. However, in an attempt to maintain some clarity, I will specifically address blockchains.

What problem do distributed ledgers solve, and how can blockchains be used to implement them? To answer the first question, we’ll study the case of a discussion forum, as a toy example. This will outline the specific problem that call for the use of distributed ledgers.

Case study: a discussion forum

Picture a typical online discussion forum: messages are posted by authenticated users in response to other messages, forming threads of discussions. Some users may be permissioned to post in certain sub-forums, or banned from doing so, and users gain karma by seeing their posts being up-voted.

It is quite straightforward to implement such a system using a single database, and many such implementations are available. If we wished to operate a decentralized forum, it might seem logical to implement it by treating a blockchain powered decentralized ledger as a database. However, examining the nature of a decentralized forum reveals that it derives few or no benefits from such an implementation:

Consider indeed the following implementation for a decentralized forum:

-

A client connects to a peer to peer network maintaining a distributed hash table. It requests a list of message headers from its peers. Using these headers, the client reconstructs the various discussion threads. Censorship may be possible if a client is isolated from the rest of the network by malicious peers, but that is also the case when using blockchains.

-

Spam may be averted using either a very nominal proof-of-work hash in message headers, or by using whitelists and blacklists maintained by popular curators.

-

Read access in sub-forums is managed in much the same way as it would be on a distributed ledger, by allowing multiple keys to decipher the content of messages.

-

Write access is ultimately at the discretion of each viewer. If a viewer decides she wants to ignore write access rules and read all of the messages that claim to be valid, she can do so without affecting anyone else. In most cases, however, she may probably want to filter messages using agreed upon permissions. A K out of N signature scheme can grant and revoke such permissions. Upvotes and downvotes can be treated as a special kind of post. They are disseminated on the peer to peer network and aggregated by each client to determine a user’s karma or a post’s visibility.

A DHT such as Cassandra, Chord, and Kademlia can power this distributed forum, there is no need for a distributed ledger.

The reason we didn’t need a blockchain to implement any of this is that all the structures we are representing on the network happen to be persistent data structures (also known as immutable data structures or, less commonly, append-only data structures). These structures are very common in functional programming languages which tend to shun the use of mutable variables.

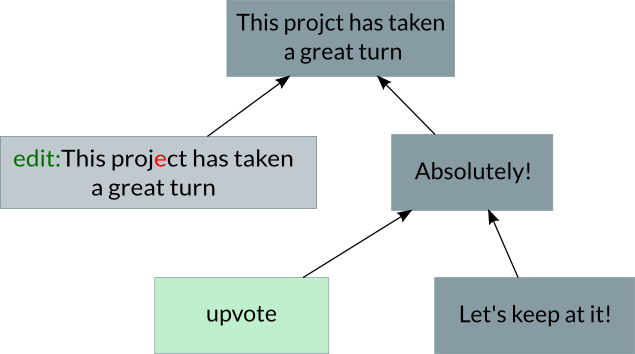

A persistent data structure often looks like a tree (more generally, a directed acyclic graph). For instance, a thread in our forum might look like this:

In this graph, a user posted a message saying the project had taken a great turn. The message was later edited for typos, two replies were posted, one of which was upvoted.

Notice how there are no loops in this graph. All of the objects attach themselves freely to previous objects. Once created, messages are never themselves modified, they are immutable. What exactly would require mutability in a forum? Three possibilities come to mind:

-

usernames

-

capping the number of permissioned users

-

time-stamping of messages

Usernames

Zooko’s triangle is a hypothesis in computer security which claims that a system cannot be decentralized, secure, and give network participants human meaningful names. Namecoin seems to be an exception to the triangle, but its security is conditional on the behavior of participants (miners) and not on mathematical principles.

Before blockchains, there were essentially two ways to deal with the problem.

-

Drop the requirement of having a consensus over the owner of a specific key. You can rely on a web of trust for each participant to decide for themselves on the association between keys and identities, or you can just accept the key value established during the first connection, as SSH encourages. Crucially, and unlike the case of a digital currency, the absence of a consensus does not matter a great deal. If I decide that I really want www.google.com to point to Microsoft’s Bing IP address on my machine, my doing so does not affect anyone else.

-

Drop the requirement of decentralization and rely on a traditional certificate authority. Participants can easily audit this certificate authority, and detect any invalid alteration of its registry as fraudulent.

We can now use a blockchain, such as Namecoin, to ensure that a single key is associated with a given name. Had we tolerated that many people claim ownership of a single username, a blockchain would have been totally unnecessary.

Lesson: blockchains can count (as in “tally”, and in this instance, count to one), DHTs cannot.

Giving permissions to a set amount of people

It should now be clear why granting specific permissions to a fixed number of people is unenforceable using append-only data structures: nodes in these graphs cannot count their children. In most forums, administrators are free to grant or deny read access to an arbitrary amount of people. However, one could imagine a scenario where a set number of people is expected to receive this right. In this case, a blockchain would be required. A forum where any three administrators can elect a new administrator can be implemented with a DHT, but if we require that there be no more than, say ten administrators, then a distributed ledger is required.

Timestamping

Depending on the application, accurate, trusted timestamping of messages can be sensitive. While messages are naturally ordered in a discussion thread, one might want to know which of two replies was first submitted in a thread. This can be achieved with a trusted timestamping service or with a blockchain. The ability to timestamp falls out of blockchains’ ability to maintain a shared state validated by the participants.

Representing mutable data structures

Variable mutation is intrinsically a physical act: when a program uses mutable variables rather than immutable variables, different phenomena takes place on the physical level. Indeed, mutations destroy information (the previous value) and thus must release heat following the second law of thermodynamics. Landauer’s principle asserts that the minimum amount of energy required to erase one bit of information is kT log 2, where T is the temperature of the system and k is Boltzmann’s constant. Erasing a bit is an irreversible operation, and as such it must increase the entropy of the universe.

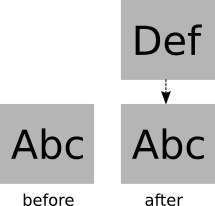

Fortunately, computer scientists invented a trick to simulate mutations without really doing mutation. Instead of erasing the old value, we simply keep it but add a new value on top of it. For instance, in the following example, the value “Abc” has been replaced with the value “Def”. We’ve represented the mutation using an append-only data structure. This is also known as a monad. We’ve essentially replaced a mutable variable with a linked list.

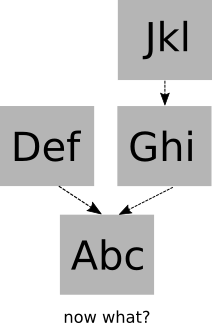

There’s just one problem, our linked list is actually a tree. Indeed, the following structure could be created, in particular if multiple parties attempt to introduce mutations at the same time. In this case, there are multiple “heads” for the list, or, alternatively multiple “leaves” in the tree.

Finding consensus

It would be very convenient if we could just keep track of “the” head of the list, but doing so would require implementing mutations, because that head keeps changing. We are back to that same problem we described earlier: we need exactly one head, a single consensus value.

The way Bitcoin solves this problem is by attaching a proof-of-work to each block. The branch with the most amount of work is deemed to be the canonical one. Economic incentives are attached to the protocol to entice miners to form a consensus and work on the same branch.

One may consider many other rules for picking a canonical branch. One could pick the branch signed by the largest amount of stakeholders, the branch with the most transaction activity, or simply the branch signed by K out of N trusted parties. What characterizes a blockchain algorithm is essentially the procedure by which it picks the consensus representing branch.

Conclusion

Blockchains aren’t merely distributed databases. They are a data structure which can be used to represent a shared, mutable, singleton. Shared because multiple parties can access it, mutable because they may modify it, and singleton because there is exactly one such value.