A functional nomenclature of cryptographic ledgers

In the interest of bringing some much-needed sanity to the discussion surrounding “blockchain technology” I have attempted to establish a functional nomenclature of cryptographic ledgers.

-

Why a nomenclature? because a lax usage of many terms, combined with an insatiable appetite for buzzwords, has crippled the discussion with vagueness.

-

Why functional? because I will attempt to describe the possible motivations for the use of certain technological choices.

English is not a prescriptive language (it is… decentralized), rendering the task of defining words somewhat subjective. I have striven to formulate definitions which map to fundamental concepts without straying too far from the common acception.

The space of cryptographic ledgers seems to be divided among four main axes:

-

distributed vs. localized

-

decentralized vs. centralized

-

permissioned vs. permissionless

-

tokenized vs. tokenless

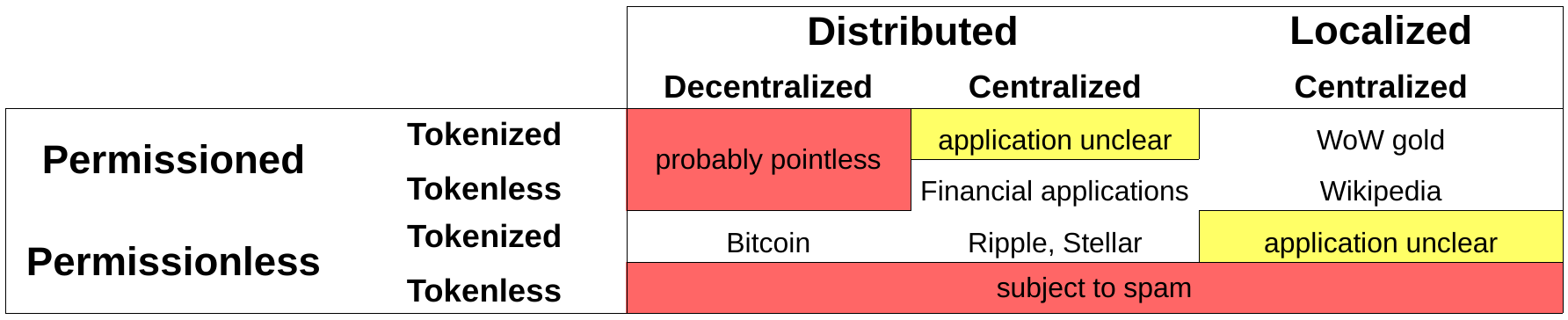

This suggests 2^4 = 16 possibilities. Of these, 12 are logically possible, but only a few make sense. In the same sense, it is possible to build a heavy 4x4 with a lightweight two-cylinder engine, but it’s unlikely to be a particularly useful combination.

I will now proceed to analyze those distinctions, their interactions, their meaning, and their raison d’être.

Distributed vs. localized

Most ledgers currently in use are localized which means that they are maintained in a single location. They are generally implemented using relational databases. The “single location” criterion does not preclude the database from being replicated, but a single record will be considered authoritative. Examples include all accounting software, Amazon gift cards (in all likelihood), etc.

In contrast, a distributed ledger is a ledger maintained by several separate entities, on different computers. This arrangement requires that the ledger maintainers follow a consensus protocol in order to maintain a consistent view of the ledger. Examples of distributed ledgers include the Bitcoin blockchain, Stellar, and more.

Localized ledgers tend to be more efficient than distributed ones and offer lower latency as there is no need to reach a consensus. Distributed ledgers offer greater resiliency in case of system failures or malicious attacks. Trading platforms, which require low latencies to attract liquidity providers, may thus benefit from being implemented on a localized ledger. The clearing and settlement process, however, which follows the trade, might be safer on a distributed ledger.

Decentralized vs. centralized

A decentralized ledger is one in which no set of participants is given *a priori *a privileged role. This does not preclude participants from taking on special roles later on, for instance through an election process, but it means that there are no specific, named, entities playing a special role in maintaining the ledger. Bitcoin is the most famous decentralized ledger.

In contrast, a centralized ledger gives specific participants particular roles. For instance, some systems specify that the ledger be maintained by a fixed set of known validators. Ledgers that rely on a local database are centralized because a single party controls the physical integrity of the hardware where the database is recorded. Certain distributed systems, such as Ripple, or Hyperledger are also centralized since they rely on a preset group of validators responsible for maintaining consensus.

Can decentralized ledger be localized? In general, no. The very idea of decentralization suggest that there are many parties maintaining the ledger, and thus that the system is distributed.

The advantages of a decentralized system over a centralized one are subtle. Typically, the advantage being presented is that one does not need to trust a set of entities, thus making the system less corruptible. However, this seriously depends upon one’s threat model.

Centralized distributed ledgers do permit the ledger maintainers to conspire to alter the ledger, however, it is possible to make such tampering easy to detect. If the validators can suffer serious, immediate, consequences for their actions, such as being thrown in jail, not much trust is actually being extended. Imagine the following situation, a set of trustworthy organizations is maintaining a distributed ledger when suddenly, they decide to alter the ledger, erasing part of its history. Immediately, a multitude of external auditors notice the change, the perpetrators are caught and thrown in prison — unless of course they are following a court order.

Conversely, Ethereum creator Vitalik Buterin has described decentralization as: “The security assumption that a nineteen-year-old in Hangzhou and someone who is maybe in the UK, and maybe not, have not yet decided to collude with each other.” Even fully benevolent operators are subject to being physically coerced into taking part in an attack on the network, an attack which may remain fully anonymous

The real advantage of decentralization isn’t in minimizing trust — in fact the risks of ledger alterations might be worse — it is in minimizing the risk of censorship. A set of known ledger maintainers can be compelled by law to censor the ledger, a decentralized application with pseudonymous participants does not suffer from this flaw.

A few evangelists have pushed forward the thesis that the innovation introduced by the Bitcoin blockchain will somehow revolutionize the practices of a plethora of existing businesses. Yet, in order to harness any benefit from a decentralized ledger, these businesses must be themselves censorship resistant. This excludes any business which isn’t operating under the secrecy of pseudonymity since a government can simply arrest its operators rather than attempt to censor their ledger.

Many individuals in the world live under oppressive regimes and could benefit a great deal from a decentralized currency such as Bitcoin. It makes complete sense to develop new businesses that can provide them with the means to secure, exchange or spend bitcoins. Those businesses need not operate under pseudonymity if the laws of the country they operate in permit their activity.

What really does not make much sense is the popular idea that large financial institutions in the US would benefit from using a censorship resistant ledger to conduct financial operations. Either the government permits their activity, and they have no need for censorship resistance, or it doesn’t, and a decentralized ledger will provide no protection against a police squad swarming their headquarters.

Of course, evangelists do not consider censorship resistant to be the only advantage. They cultivate the myth that Bitcoin solved the comparatively easier problem of maintaining a distributed ledger. For example, Marc Andreesen writes in the New York Times:

“Bitcoin is the first practical solution to a longstanding problem in computer science called the Byzantine Generals Problem”.

That is simply not the case. PBFT (Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance) predates Bitcoin by almost a decade, and the first practical solutions appeared in the early 1980s, more than thirty years ago.

Decentralized applications have a tremendous potential to help all the individuals living under oppressive governments because that is what they are designed for. Applications which do not attempt to evade oppressive governments have little or no reasons to use decentralized systems.

Permissioned vs. permissionless

Decentralized ledgers such as the Bitcoin blockchain are permissionless. This means that anyone can participate in Bitcoin without having to ask anyone else for permission. In contrast, permissioned systems are closed gardens that only a specific set of participants are allowed to access.

The question of permissioned vs. permissionless system often comes up when discussing the use of distributed ledger in the financial industry. It is sometimes assumed that KYC requirements imply that any such system needs to be permissioned, but this needs not be the case. As Richard Brown suggests, it is quite possible for the participants in this system who need to perform KYC verifications to only interact with the participants who have verified themselves in such a way. It is also possible to specify that a security or a contract represented on such a ledger may never be held by any unidentified party.

A permissionless ledger provides a potentially more vibrant ecosystem by encouraging the development of innovative services. The web is a typical success story for permissionless innovation, and comparisons between permissionless decentralized ledgers and the web abound. Note that the web, though largely permissionless is in fact centralized, through the root DNS system.

That being said, there are several advantages to a permissioned system. If questionable activities take place on a permissionless ledger, some participants may worry that it might taint their reputation by mere association. More importantly, a permissioned system makes dealing with the problem of spam, and denial of service attacks easier by several orders of magnitude.

Permissioned systems are typically centralized. It is possible to build a permissioned ledger on top of a decentralized ledger, but pointless. If you are dealing with a close network of known participants, there is no need to incur the risk and complexity of inviting everyone else to weigh in on the consensus.

Likewise, using Bitcoin’s proof-of-work algorithm to power a permissioned system is possible but pointless when there exist simpler and safer alternatives.

Tokenized vs. tokenless

Many of the ledgers that have sprung up in the wake of Bitcoin’s success rely on a native token to function. By native token, we mean a purely digital asset represented within the ledger. In Bitcoin, those tokens are known as bitcoins, in Ethereum as ethers, in Ripple as XRP, etc. Non-native assets, such as government issued currencies, cannot directly be embedded in those networks, but liabilities in such assets can. Native tokens, however, do not represent a liability, they are bearer assets.

These tokens typically serve two main purposes:

-

They act as an economic incentive for the protocol participants to form consensus in decentralized systems

-

They help prevent spam and denial of service attacks

Economic incentives

Forming economic incentives within a consensus protocol is really only relevant for decentralized systems. In centralized system, financial penalties for breaking the consensus can be assessed outside of the protocol. For instance, in Bitcoin, a miner who mines a block outside of the consensus will spend energy and forego his reward. The penalty here is internal to the system. In a centralized system with known validators, the penalty for cheating the consensus can exist in the form of legal consequences, or the forfeiture of a bond denominated in a government-issued currency.

Though Bitcoin first introduced the idea of using economic incentives to push the maintainers of the ledger towards maintaining a consensus, other designs have followed suit, such as the ones based on proof-of-stake. The design of these consensus algorithms for decentralized systems is complex and fundamentally empirical. The guarantees of consensus aren’t given by mathematical theorems, but by an economic analysis of the incentive of the different actors. The successful interplay between cryptographic techniques and economic incentives hinges on many assumptions, and empirical evidence is ultimately needed to evaluate the workability of the scheme.

In contrast, the design of consensus algorithms for centralized ledgers is almost pure engineering, and the validity of the algorithms involved can be expressed in a mathematical framework and formally proven.

This is not to say that the consensus algorithms involved in distributed systems are trivial! They are the subject of active research in order to improve their robustness and scalability. However, their behavior is much better understood as there are fewer discretionary elements at play.

Spam and DoS prevention

In an online contest held by Wal-Mart, the Wal-Mart store receiving the most online votes would host a Pitbull concert. Kodiak, Alaska won. Such pranks may be amusing, but they illustrate a certain weakness of permissionless systems.

A permissionless ledger can be targeted by denial of service attacks and spam. What is to prevent someone from performing a trillion transaction? Or for submitting millions of complicated transactions to the ledger every second? The ledger is a limited resource, what is to prevent abuse?

I suspect that most people vastly underestimate the amount of ingeniosity that goes into Bitcoin in order to thwart denial of services attacks and spam. For instance, inspecting the potential validity of a block is a lightweight operation which merely requires looking at a few bits. Forging invalid blocks that can pass this simple test would be extremely expensive, and thus would not be of any use in attempting to choke the network. And this is just one of the ways with which spam is handled!

In general, tokens can be used to thwart spam in permissionless ledgers. They may not handle spam at the network level, but they do handle it within the ledgers. This means that they may not prevent someone from trying to submit a billion invalid transactions, but they can prevent someone from submitting a billion valid transactions.

If every operation carries a nominal fee, regular users may barely notice the costs of operating, but spammers can be thwarted by the huge cost involved in creating a large number of transactions. Small proofs-of-work can be used in lieu of tokens, but this is inherently less efficient than transferring valuable tokens to the maintainers of the ledgers as a subsidy.

Permissioned systems do not necessarily need tokens, as spammers and abusers can be identified and banned from the system relatively easily. Permissionless systems and decentralized systems probably do need a token to operate correctly.

Conclusion

There are many possible combinations of the technology, and I think only a few are useful:

-

Localized, centralized, permissioned, tokenized: WoW gold

-

Localized, centralized, permissionless, tokenless: Not really a ledger, but Wikipedia

-

Distributed, centralized, permissionless, tokenized: Ripple, Stellar

-

Distributed, centralized, permissioned, tokenless: financial application

-

Distributed, decentralized, permissionless, tokenized: Bitcoin, etc